Taxation of Capital Income Is Not Race Neutral

|

This post was originally published on TaxVox, the blog of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

The Internal Revenue Code generally does not refer to race or ethnicity, but federal income taxes may contribute to racial disparities when factors that affect tax liabilities are associated with race. Historically, it has been difficult to assess those effects because of the absence of data linking tax liabilities to race and ethnicity.

But using the Tax Policy Center’s enhanced tax model overcomes that challenge, shedding light on not just the current effects of longstanding policies but also potential changes to the tax code.

In our new report, we find that the current tax treatment of capital income favors White families over Black families for three key reasons. First, certain types of capital income are effectively taxed at lower rates than many other forms of income, such as wages and salaries. Second, Black families on average have substantially less wealth than White families and thus have fewer opportunities to take advantage of those lower rates and many other tax preferences. Third, even among those with similar incomes and wealth, Black families are at a disadvantage because their asset portfolios are less skewed toward tax-preferred assets.

Some changes to the tax code—such as raising the tax rates on capital gains—could narrow racial discrepancies in families’ after-tax income. But the story is more nuanced when it comes to the tax treatment of families’ homes.

Tax treatment of capital income

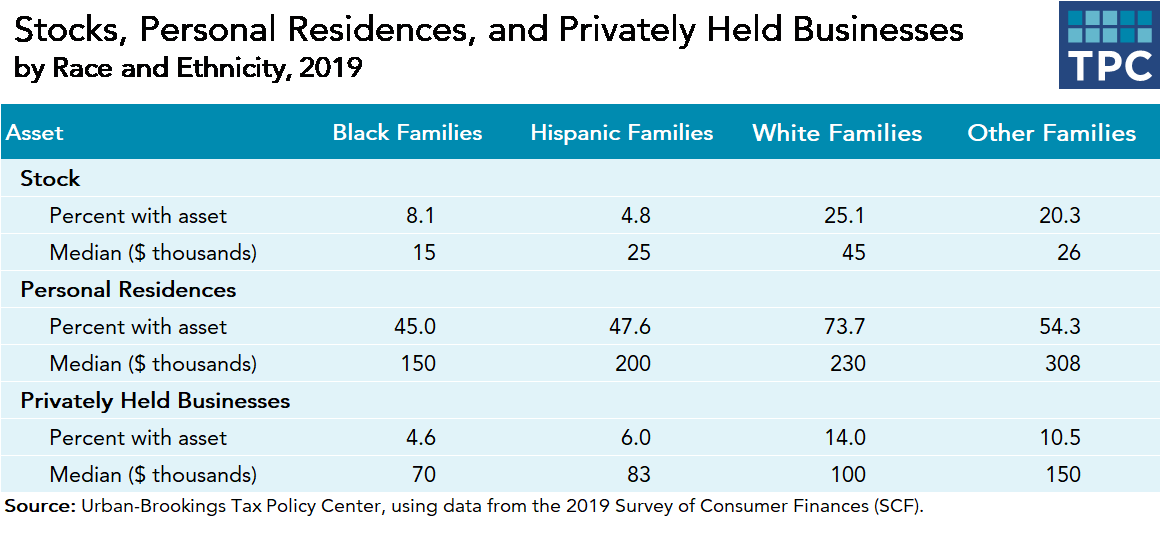

In 2019, nearly half of families’ gross assets consisted of stocks and personal residences. Both assets receive preferential treatment under the tax code. Most dividends and long-term capital gains—the net proceeds from the sales of capital assets held for longer than a year—are taxed at lower rates than many other sources of income, including wages and interest. And, up to a threshold, capital gains from the sale of personal residences are exempt from taxes. Taxpayers who itemize can also deduct their home mortgage interest.

Those tax preferences are most valuable to higher-income families, in part because the size of the tax breaks increase as families move into higher tax brackets.

Racial wealth gap

Black families, however, are less likely than White families to benefit from those tax preferences since they own fewer assets. In 2019, the median net wealth of White families was $189,100, versus $24,000 for Black families.

The racial wealth gap persists within income groups. In the middle-income quintile, the net wealth of White families averaged $345,100 compared to $130,200 for Black families in 2019. Even in the top income quintile, the net wealth gap was wide, with average net wealth totaling $4.4 million for White families and $1.4 million for Black families.

Portfolio composition

Also striking are differences in the composition of investment portfolios. Stock holdings represented 4 percent of gross asset value for Black families, compared to over 13 percent for White families in 2019. Within each income quintile, the average amounts of capital gains and dividends were also higher for White families than for Black families.

The data on homeownership are more ambiguous in their implications for the racial incidence of the mortgage interest deduction. About three-quarters of White families owned their homes versus less than half of Black families in 2019. Overall, White families were also more likely to have a mortgage than Black families. Both findings suggest that the mortgage interest deduction is more valuable to White families than to Black families.

However, the prevalence of mortgages among Black families in the highest income quintile—where the tax benefits of the mortgage interest deduction would likely be greatest—is substantially higher than for White families (84 percent and 71 percent, respectively, in 2019). Black families in the top income quintile were also more likely to make mortgage interest payments than White families.

Changes to the tax treatment of investment income

Changes to the tax code in 2019 could have helped mitigate the racial disparities caused by the tax treatment of capital income, though the effects may be less clear-cut than they may at first appear.

Raising the tax rates on long-term net capital gains in 2019 would have disproportionately increased taxes on White families. The relative burden on White families would have been greater if the increased capital gains rates applied only to higher-income taxpayers, whether that threshold was measured by being in the top income tax bracket or by earning more some threshold, such as $1 million. However, in general, taxpayers may be able to avoid the tax increase by not realizing their capital gains.

Replacing the home mortgage interest deduction with a 12 or 22 percent nonrefundable tax credit would have increased the overall progressivity of the individual income tax. In the first four quintiles of the income distribution, taxes would have fallen for all families. White families would have, on average, received a disproportionate share of the benefits. Because the value of the tax credit is less than the value of the deduction for higher-income families, the top 5 percent of the income distribution would have faced tax increases, on average.

But a disproportionate share of those tax hikes would have fallen on Black homeowners in this income group, due to their greater reliance on outside financing to purchase a home. Other research suggests a reason for that result: Black families are less likely to receive inheritances or cash assistance from relatives than White families.

Our findings demonstrate how examining the tax code through the lens of race and ethnicity in addition to income can yield new insights on questions such as how to improve fairness and efficiency.

Posts and comments are solely the opinion of the author and not that of the Tax Policy Center, Urban Institute, or Brookings Institution.

Related Projects

-

September 28, 2016

|Has Evidence

| -

Mental and Behavioral HealthCalifornia Diversion: Mental Health, Racial Equity, and Criminal Court

December 14, 2021

|Has Evidence

| -

Community Justice and Public SafetyAre Cities and Counties Ready to Use Racial Equity Tools to Influence Policy?

January 14, 2019

|