Whether through Medicaid or private insurance, having coverage is consistently tied to improved medical care access

|

For decades, Medicaid has provided virtually no-cost coverage to millions of Americans priced out of the private insurance market.

Still, state legislators, policy analysts, and the popular press continue to question Medicaid’s value, particularly in relation to private coverage. Twelve states have not expanded Medicaid coverage under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) framework despite the offer of federal funding to cover 90 percent of the costs associated with the additional enrollees. Other states have experimented with reforms that make the Medicaid program function more similarly to private insurance, including requiring enrollees to pay premiums to enroll and pay cost sharing to seek care. By contrast, some policymakers in other states are considering establishing a Medicaid buy-in as a public option for health insurance, which would effectively expand Medicaid coverage beyond the ACA expansion population.

Behind these very different policy directions are enduring empirical questions about the quality of the coverage Medicaid provides. The public and scholars alike remain unsettled on whether Medicaid adequately delivers needed medical care for its low-income beneficiaries; whether such care is on par with that accessed through private insurance; and whether, as some have argued, Medicaid is even worse than having no coverage at all.

Our Policies for Action project examines these questions directly. Are beneficiaries with Medicaid getting to the doctor when they need to? Or are they less able to access care than they would be with private coverage?

What do we know about how healthcare access differs under Medicaid versus private insurance?

Numerous studies have shown substantial gains in healthcare access, health coverage, and financial stability for Medicaid beneficiary populations newly eligible through expansion relative to their counterparts in states that have not expanded Medicaid. These studies help inform state expansion decisions by comparing Medicaid with the mix of coverage types found in the absence of expansion, including private insurance and high rates of uninsurance. A handful of other studies have more directly compared Medicaid and private insurance by looking at people whose incomes are very close to the Medicaid income cutoff, comparing the highest-income Medicaid enrollees with the lowest-income private insurance enrollees. The findings are not entirely clear. One study looked at a very narrow income band, spanning only a few hundred dollars’ difference in annual income, and found small but significant differences in healthcare use. Another looked at a wider income group, spanning $5,000, who would get Medicaid in expansion states and who would get subsidized Marketplace coverage in nonexpansion states. The study saw no differences in healthcare use but did find that the expansion states made less progress toward making it easier to find a provider.

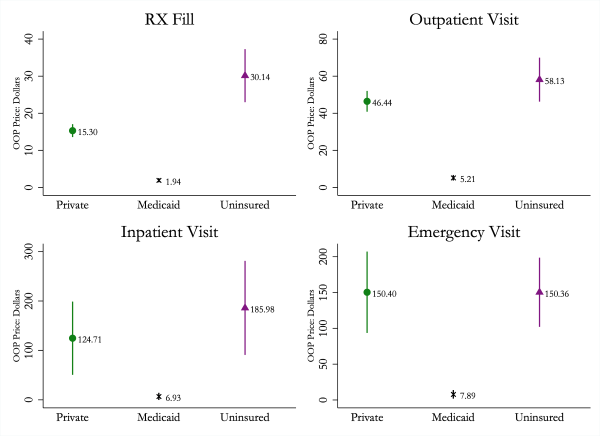

One substantial and consistent finding has been that the out-of-pocket costs Medicaid enrollees face when accessing care are meaningfully lower than such costs faced by people with private insurance. Out-of-pocket prices matter more and more for households with incomes nearer to and below the poverty level. This could mean that the financial barriers of private insurance would weigh more heavily on the full Medicaid beneficiary population than on the population with incomes at or near the poverty level examined in these comparisons.

What is Medicaid’s value for households in poverty?

When we compare households with incomes near and below the poverty level, who constitute the Medicaid population, with the nearly 18 million Americans with similar low incomes who have private insurance (nearly 9 million of whom live in poverty), we find that both groups access about the same number of provider visits across a range of settings and similar numbers of diagnostic tests. We also estimate that, on average, those with Medicaid are slightly, but significantly, more likely to have a usual source of healthcare that is not an emergency department and filled more prescriptions on average than their privately insured counterparts. These estimates account for medical differences and differences in economic and social backgrounds that might have otherwise explained these patterns (to the extent possible in an observational study).

Though healthcare use was more alike than different between the adults with incomes at or near the federal poverty level with public and with private coverage, we found that both groups got consistently, substantially, and significantly more care in nearly every service category, including primary care and specialist office visits and diagnostic tests, than the uninsured population.

These results and the literature to which they add illustrate the importance of expanding coverage, whether through public or private channels. Medicaid cannot earnestly be considered worse than being uninsured in terms of accessing care. Instead, Medicaid is nearly indistinguishable from private insurance, particularly among Medicaid beneficiaries with the lowest incomes.

Still, work remains to make access to care more equitable for Medicaid beneficiaries

We found that Medicaid enrollees ultimately access a similar level of care as their privately insured counterparts. Nevertheless, studies have shown that Medicaid beneficiaries have more difficulty obtaining doctor’s visits and other healthcare services than do people with private coverage. These difficulties are called “nonfinancial barriers” and include difficulties like having to wait several weeks for the next available appointment. It is possible, perhaps even likely, that without these nonfinancial barriers, Medicaid beneficiaries would use more healthcare than, rather than simply using the same amount as, people with private insurance.

One of the most basic ideas of economics is that when prices goes down, demand goes up. Studies, most notably the RAND Health Insurance Experiment, have shown that the same holds true in healthcare. Given that Medicaid charges its beneficiaries very little, if such coverage were the same as private insurance in every other way, we would expect Medicaid beneficiaries to use more healthcare.

Average Out-of-Pocket Expense per Episode of Care, by Insurance Status

Notes: Data are from the 2014–17 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey and include adults ages 19 to 64 with continuous insurance status and income no greater than 150 percent of the federal poverty level. The figure plots the mean out-of-pocket expense per episode of care among individuals with at least one such episode by insurance status. Data are weighted using entropy weights estimated to balance demographic covariates across insurance types.

Nevertheless, we observe that even with these lower costs of care, Medicaid beneficiaries end up using about the same level of services as their otherwise similar counterparts with private insurance, who face higher prices for care. The results suggest that the difficulty of obtaining care documented among Medicaid beneficiaries owes to nonfinancial barriers that, in practice, mirror the financial barriers to care observed among privately insured people with low incomes.

The glass is half empty, but it’s also half full

Taken together, the study results suggest that by delivering medical care to households with incomes at or near the poverty level, Medicaid is performing a critical function, and we have no reason to believe it does so substantially less effectively than the alternative private system does. This information can help inform policymakers, particularly those in nonexpansion states, where expanding this form of coverage will likely substantially improve lives.

The results also fail to let us, as policy scholars and analysts, entirely off the hook.

We have work to do in finding better care delivery systems for enrollees in public coverage. Simply modeling Medicaid closely after private insurance, which weighs improved provider access against the added costs of seeking care, is unlikely to yield progress in access to care. Nevertheless, we have room for more research into the kinds of care delivery models that work the best across states, such as primary care capitation, public or private managed care, and fee-for-service models. Research on other ways to define and overcome the nonfinancial barriers to care Medicaid beneficiaries may experience is also needed.

Support for this research was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Policies for Action program. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation.

Related Projects

-

September 28, 2016

|Has Evidence

| -

Mental and Behavioral HealthCalifornia Diversion: Mental Health, Racial Equity, and Criminal Court

December 14, 2021

|Has Evidence

| -

Community Justice and Public SafetyAre Cities and Counties Ready to Use Racial Equity Tools to Influence Policy?

January 14, 2019

|